Alla Biennale di Venezia, è possibile visitare l’interessante Padiglione del Nepal, con le opere dell’artista Ang Tsherin Sherpa. Esteticamente, egli esibisce le contraddizioni storiche e culturali dell’Himalaya. Se esiste il nomadismo d’una spiritualità, partendo da una tradizione locale, si rischia fatalmente d’occidentalizzarne la mercificazione, tramite il ritiro… d’una “cartolina”? Da un lato si narra l’intreccio delle religioni (il bonismo, il buddismo, l’induismo ecc…); dall’altro lato si rincorre l’idillio del new-age in una Shangri-La. Virtualmente, l’altopiano consente una protezione anche per il tetto. Però sarà impossibile evitare di percorrerne lo scolo, grazie alla vallata. Se “ci affacciamo” alla spiritualità, nel contempo la vitalità “si timbra”. Alla circonferenza per la “sfera” della personalità, l’anima “si scola” tramite la pressione dei sentimenti. In un altopiano, appare il “timbro” delle vette. Se l’affacciarsi abbraccia, in mezzo al prato sottostante, allora il “punzecchiamento” dei passi si prolungherà al ricordo d’una sentimentalità, grazie alle vallate. Il ritiro in montagna “timbra” la vitalità che finalmente può “affacciarsi”. Bisogna riscoprire la propria interiorità. Tornando a valle, avremo imparato a vivere in modo “panoramico”, ossia seguendo lo “scolo” delle nostre azioni. Nella “piramide sociale”, chi raggiunge la punta poi si prende una… “valanga” di responsabilità. Gli Altri potranno ammirarlo, nel suo modello di scudo. A Venezia, la mostra di Ang Tsherin Sherpa s’intitola Tales of muted spirit + Dispersed threads + Twisted Shangri-La. L’artista avrebbe ricostruito un nomadismo antropologico, in Nepal. Accadde che gli Sherpa emigrassero dal Tibet, miticamente seguendo un anelito, anziché una stella (nel contesto d’un altopiano col clima rigido). Da quello s’arriverà per antropomorfizzazione allo spirito. Nel complesso l’artista avrà ricavato il nomadismo d’una formazione culturale. Gli spiriti dell’altopiano non saranno più invisibili, potendo lasciare la loro impronta, grazie al simbolismo estetico. L’animismo delle vette, utile ad affacciarsi sulla “panoramica” d’una vitalità, pare la “linfa” per la gronda d’una tradizione culturale. L’esistenza ci chiede di valicare sempre un nuovo “passo”. Così, per ricordarsi l’origine antropologica, l’altopiano è simbolicamente ringraziato, predisponendo un’offerta rituale. L’idillio nepalese non può banalizzarsi nel turismo occidentale, modernamente. La montagna, cui ritirarsi in segno di rispetto per la “bellezza miracolosa” della vita, a volte può uccidere: dalle valanghe, per il congelamento, disorientando ecc… Anche agli albori dell’Occidente, le divinità erano “catalogate” in base all’imprevedibilità delle proprie passioni, sino al banale capriccio. Modernamente, la fredda società del razionalismo può nutrire qualche pregiudizio, in merito alle comunità rurali “di confine”. L’isolazionismo comporta il conservatorismo (“ingelosendosi” per nulla, alla ridicolaggine). Ma potrà diventare “beffarda” pure la vitalità urbana, oltre l’illusione d’avere ancora un Piano B in mano, contro il primo insuccesso. Il nomadismo antico tramuterà nella flessibilità moderna? Quello fra le alte vette quantomeno permetterebbe di liberare la propria spiritualità, senza subire il calcolo della società materialistica. Per l’esibizione a Venezia, Ang Tsherin Sherpa ha collaborato con altri artisti dal Nepal.

La scultura in bronzo dal titolo Muted expressions raffigura un groviglio d’arti umani, sintetizzati al culmine del piede e della mano. Nell’insieme, si percepisce che per vivere bisogna “calpestare un possesso”. Si cammina sempre in cerca d’una meta. Nell’altopiano, l’intreccio delle vette può confondere l’orientamento. Forse il passo funge da “maniglia”, per aprire una “porta” direzionale. La scultura di Ang Tsherin Sherpa pende dal telaio d’un ponteggio. Una rete paramassi avrebbe intercettato i raggi vitali del sole. Si percepirebbe il fango dorato del cammino, quando, mediante lo spirito, noi possiamo sopportare la fatica di raggiungere la meta prefissata. Virtualmente, anche dalle ossa si staccheranno dei detriti. La scultura è sorretta, per cui ci ricordiamo delle ferrate più o meno “adrenaliniche”, lungo i versanti impervi. Lo scalatore abbisogna di contorcere il suo corpo, a volte. Il calpestare appare vitale, perché l’alternativa diventa il pericolosissimo salto nel vuoto. In alta montagna aumenta l’intensità delle radiazioni solari. Quella ovviamente “si timbra” sull’abbronzatura. La confusione fra le mani ed i piedi simboleggia il trasporto. A prescindere dall’isolato (ma non inospitale!) Nepal, una semplice bustina di tè sarà prodotta anche per il mercato occidentale. In chiave più spirituale, l’abbronzatura tenderà a “distorcere” il nostro sforzo di scalare il cielo.

L’installazione dal titolo Entangled threads presenta un telaio da tessitura. Ang Tsherin Sherpa spiega che il consumismo occidentale ha raggiunto anche il Nepal. Molte donne producono tappeti per l’esportazione. Gli approfittatori raggiungono i villaggi remoti millantando una nuova spiritualità, legata alle promesse d’un benessere sociale. Le tecniche tradizionali di lavoro si scontrano coi “capricci” del trend affaristico. Il disegno del tappeto esposto da Ang Tsherin Sherpa non è concluso. Quasi percepiamo un effetto farfalla, con due ali tigrate che si sbattono, e sino a causare lo scioglimento d’un nevaio. C’è soprattutto la “caduta massi” dei gomitoli, sul pavimento. Chissà quanto l’aumento speculativo d’una frequenza produttiva riuscirà ad “ingabbiare” una desolazione selvatica! La solarità d’alta quota contraddirà la purezza d’uno spirito trasceso. I gomitoli non sembrano in grado di “timbrare” il “decorso” dell’opera. La valanga dal pendio “distorce” la concavità dell’altopiano. Forse la commercializzazione va troppo di fretta, impedendo alla tradizione artistica di curare il dettaglio.

Per il filosofo Francesco Tomatis, la valle è sempre “gradita” all’escursionista, ed in quanto rigogliosa di riflesso, universalizzando, al coinvolgimento della Terra, una “corolla” del cielo, fra i “petali” delle alte vette. Non vi funziona solo l’incanalamento vacuo d’una necessità unidirezionale (dal pendio). Scendendo, verso la pianura, è abbastanza comune l’esperienza di guardare all’indietro. L’approdo all’interiorità, sulla cima montuosa (da cui si vive sul serio: a 360°, in una “panoramica” della propria coscienza) avrà rappresentato un momento eccezionale, degno di “rispetto”. Si può immaginare una sorta di “catarsi” per il nomadismo? Quando la coscienza scopre se stessa mediante l’interiorità (per una completezza della vita spirituale, fra la percezione e l’intellezione), abbiamo imparato a “scavare” anche la “normalità” dell’esteriorità materiale. In chiave esistenzialistica, ricorderemo con affetto la vetta raggiunta al fine di responsabilizzare gli Altri, su un percorso che loro non potranno evitare d’affrontare.

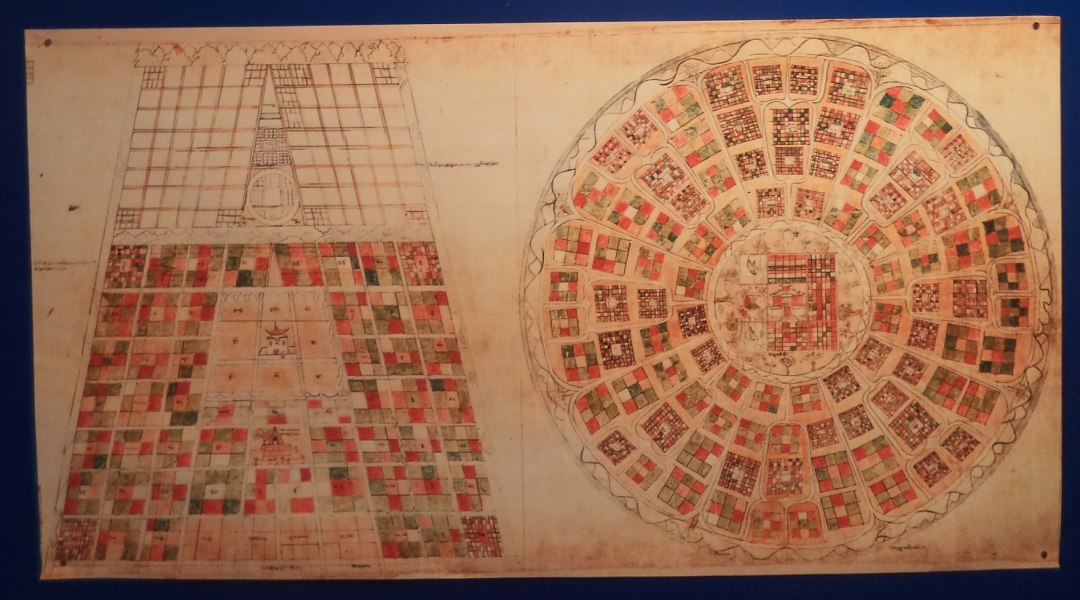

Nella stampa digitale dal titolo Details from Kalachakra cosmos, si cita un rito del buddismo tibetano. Quello consente di “far ruotare” il corpo umano, virtualmente a livello terrestre. Ci si basa sulla corrispondenza che alcuni fra i nostri organi terrebbero coi principali elementi in natura. Modernamente, gli Occidentali si sono un po’ illusi di poter “scappare” dai loro problemi, riscoprendo la sapienza degli Orientali. Bisogna sottolineare che il buddismo invita ad un’estrema sincerità con se stessi, sino ad abbandonare le passioni. In una ruota del tempo, immaginiamo che gli organi del corpo servano, come le pale, a “scolare” il vissuto. E’ un’attivazione energetica, che però deve riequilibrare il coinvolgimento dell’esteriorità. Allora immagineremo le alte vette al “timone” dello scalatore. La “strada panoramica” sarà quella verso uno spirito del mondo. Bisogna accettare l’ineluttabilità per cui la vitalità ha i suoi cicli, dalla nascita alla morte. Guardando al pannello della mostra, sappiamo che, secondo la tradizione, simbolicamente al Kalachakra s’accompagna l’iconografia del Monte Meru, al centro del mondo, e dei quattro cerchi sui principali elementi in natura. I toni caldi vi conferiscono una discreta energia. Nell’insieme, si cerca una dialettica fra la piramide ed il cono: la stessa che appartiene all’altopiano, geograficamente, oppure al timone sulle onde, spiritualmente.

A Venezia, il quadro dal titolo 24 views of luxation è ad acrilico su tela. Immaginiamo di ricostruire un mito, partendo dall’iconografia centrale del Khyung. Questo è presente, come un uccello dalle sembianze in parte umane, sia nell’induismo sia nel buddismo. Nel complesso, dovrebbe uscire la forma d’un “amuleto”, che protegga dalle malattie o dalle avversità. L’animismo del Khyung s’utilizza in una “scarica”. Precisamente, Ang Tsherin Sherpa ricorda l’amuleto che si chiama Thogchag. Nell’altopiano, più facilmente siamo esposti ai fulmini. L’animismo del Khyung “si scarica” pure nello spiritualismo d’una cultura. Ci si protegge in aggiunta da un antagonista: il Naga per uomo-serpente. Ma, se (dialetticamente) l’amuleto è anche persecutorio, si può capire quanto all’artista prema smitizzare l’idillio del ritiro himalayano, in pace e solitudine, secondo la banalizzazione del turismo occidentale. Il quadro esposto a Venezia avrebbe “distorto” la sua narrazione. Un’eventuale centauromachia in “salsa” nepalese sarebbe stata dipinta esteticamente fra il cubismo ed il surrealismo. Nell’insieme, si tratta di decostruire una mitizzazione (coi toni fosforescenti che funzionerebbero da “spia” per l’occidentalizzazione falsamente selvaggia). Si noti il dettaglio delle ventiquattro “tessere”. Così la “bella” vetrata perde il raccoglimento nel salone, ed al massimo “rimpicciolisce”, col proprio schermo, la facciata in strada che ha le insegne al neon, per la pubblicità.

IF WE “LOOK OUT” ON THE SPIRITUALITY, IN THE SAME TIME THE VITALITY “IS STAMPED”

At the Venice Biennale, we can visit the interesting Nepal Pavilion, with the art works of Ang Tsherin Sherpa. Aesthetically, he shows the historical and cultural contradictions of the Himalayas. If the nomadism of a spirituality exists, starting from a local tradition, do we fatally risk that we westernize its commercialization, through the collection… of a “postcard”? On the one hand a twine of the religions is narrated (the Bon, the Buddhism, the Hinduism etc…); on the other hand we pursue the idyll of the New Age in a Shangri-La. Virtually, a tableland allows a protection also for the roof. However we could not avoid travelling along its drainage ditch, through the wide valley. If “we look out” on the spirituality, in the same time the vitality “is stamped”. At the circumference for the “sphere” of the personality, the soul “is drained off” through the pressure of the feelings. In a tableland, the “stamp” of the tops appears. If we look out with an embrace, in the middle of the underlying meadow, so the pricking of the steps will be prolonged at the recollection of a sentimentality, through the wide valleys. A retreat in the mountains “stamps” the vitality that finally can “look out”. We need to rediscover our inwardness. Returning to the valley, we will have learned to live in a “panoramic” way, namely following the “drainage ditch” of our actions. In a “social pyramid”, somebody who reaches the point then takes an… “avalanche” of responsibility. The Others could admire him, in his model of a shield. In Venice, the exhibition of Ang Tsherin Sherpa is called Tales of muted spirit + Dispersed threads + Twisted Shangri-La. The artist would have rebuilt an anthropological nomadism, in Nepal. It happened that the Sherpa emigrated from Tibet, mythically following a breath of life, instead of a star (in the context of a tableland with a harsh climate). From that one, and through an anthropomorphization, a spirit will be originated. Overall the artist would have obtained the nomadism of a cultural education. The spirits of the tableland will no longer be invisible, able to leave an imprint, through the aesthetic symbolism. The animism of the tops, useful to look out on the “panning shot” of a vitality, seems the “sap” for the eave of a cultural tradition. The existence asks us to “overpass” always in a new situation. So, to remember the anthropological origin, the tableland is symbolically thanked, prearranging a ritual offering. The Nepalese idyll can not be trivialized by the Western tourism, in a modern way. The mountain, where we go into retreat as a sign of respect for the “miraculous beauty” of the life, sometimes can kill: by the avalanches by the frostbite, by the disorientation etc… Also at the dawn of the West, the divinities were “catalogued” according to the unpredictability of the own passions, until the banal tantrum. In a modern way, the cold society of the rationalism can harbour some prejudices, about the rural “boundary” communities. The isolationism entails the conservatism (when we “become jealous” for nothing, in a ridiculousness). However, also the urban vitality could become “mocking”, beyond the illusion of having still a Plan B in our hands, against the previous failure. Will the ancient nomadism be transmuted in the modern flexibility? A nomadism between the high tops at least would allow releasing the own spirituality, without suffering the calculation of a materialistic society. For the exhibition in Venice, Ang Tsherin Sherpa collaborated with other artists from Nepal.

The bronze sculpture called Muted expressions represents a tangle of human limbs, synthetized at the peak of the foot and the hand. Overall, we perceive that we need to “step on a possession”, if we want to live. We always walk searching for a destination. In the tableland, the twine of the tops can confuse the orientation. Maybe the pass functions as a “handle”, to open a directional “door”. The sculpture of Ang Tsherin Sherpa hangs from the framework of a scaffolding. A rockfall netting would have intercepted the vital beams of the sun. We would perceive the golden mud of the walk, when, through the spirit, we can tolerate the trouble of reaching the set destination. Virtually, also from the bones some debris will be detached. The sculpture is supported, so we remember the fixed rope routes, more or less “adrenalinic”, along the impervious mountainsides. A climber needs to contort his body, sometimes. The act of stepping on seems vital, because the alternative becomes a very dangerous jump into the air. In the high mountains the intensity of the solar radiation grows. That one of course “is stamped” on the tan. The confusion between the hands and the feet symbolizes the transport. Regardless of the isolated (but not inhospitable!) Nepal, a simple tea bag will be produced also for the Western market. From a perspective more spiritual, the tan will tend to “distort” our effort of climb the sky.

The installation called Entangled threads presents a loom. Ang Tsherin Sherpa explains that the Western consumerism reached also Nepal. Many women produce carpets for exportation. The profiteers reach the remote villages bragging about a new spirituality, connected to the promises of a social welfare. The traditional techniques at work “bump into” the “tantrums” of the business trend. The drawing of the carpet exposed by Ang Tsherin Sherpa is not concluded. Almost we perceive a butterfly effect, with the two tiger skin wings that flap, and until they cause the melting of a snowfield. There is principally the “rockfall” of the balls of yarn, on the floor. Who knows how much the speculative growth of a productive frequency will be able to “cage” a wild desolation! The sunshine at high altitude will contradict the purity of a transcended spirit. The balls of yarns don’t seem able to “stamp” the “course” of the art work. The avalanche from the slope “distorts” the concavity of the tableland. Perhaps the commercialization goes too fast, not allowing the artistic tradition to take care of the details.

According to philosopher Francesco Tomatis, a valley is always “appreciated” by a hiker, because it is luxuriant reflexively, and in its universalization, at the involvement of the Earth, for a “corolla” of the sky, between the “petals” of the high tops. There not only the vacuous channelling of a unidirectional necessity (from the slope) functions. Descending, into the plain, the experience in looking backwards is quite common. A landing place at the inwardness, on the mountaintop (from which we live seriously: with 360 degree, in a “panning shot” of the own consciousness) would have represented an exceptional moment, worthy of “respect”. Can we imagine a sort of “catharsis” of the nomadism? When the consciousness discovers itself through the inwardness (for a completeness of the spiritual life, between the perception and the intellection), we have learned to “dig” also the “normality” of the material exteriority. In key existentialist, we will remember fondly the reached top in order to responsibilize the Others, about a path that they could not avoid undertaking.

In the digital print called Details from Kalachakra cosmos, it is mentioned a ritual of the Tibetan Buddhism. That one allows the human body to “rotate”, virtually on the earthly level. It is based on the correspondence that some of our organs would have with the main elements in nature. In a modern way, the Westerners have deceived themselves with the possibility to “escape” from their problems, rediscovering the sapience of the Oriental people. We have to underline that the Buddishm invites us to an exceptional sincerity with ourselves, until we abandon the passions. In a wheel of time, we imagine that the organs of the body serve, like the blades, to “drain off” the living. This is an energetic activation, that however has to rebalance the involvement of the exteriority. So we will imagine the high tops at the “wheel” of the climber. The “panoramic road” will be present into a spirit of the world. We have to accept the ineluctability for which the vitality has its cycles, from the birth to the death. Watching the panel of the exhibition, we know that, according to the tradition, symbolically the Kalachakra is accompanied by the iconography of Mount Meru, at the center of the world, and of four circles about the main elements in nature. The warm tones confer there a decent energy. Overall, a dialectic between the pyramid and the cone is sought: the same that belongs to a tableland, geographically, or to the wheel on the waves, spiritually.

In Venice, the picture called 24 views of luxation is in acrylic on canvas. We imagine the reconstruction of a myth, starting from the central iconography of the Khyung. This is present, as a bird with the features partly human, both in the Hinduism and in the Buddhism. Overall, the shape of an “amulet” should peep out, to protect from the diseases or from the adversities. The animism of the Khyung is used in a “discharge”. Precisely, Ang Tsherin Sherpa remembers the amulet called Thogchag. In a tableland, more easily we are exposed to the lightning. The animism of the Khyung is also “discharged” in the spiritualism of a culture. There is in addition a protection from an antagonist: the Naga as snake-man. However, if (dialectically) the amulet is also persecutory, we can understand how much the artist is interested in debunking the idyll of a retreat in the Himalayas, in peace and in isolation, according to the banalization of the Western tourism. The picture exposed in Venice would have “distorted” its narration. A potential centauromachy in the “manner” of Nepalese people would have been painted aesthetically between the cubism and the surrealism. Overall, it has to do with a deconstruction of a mythologization (with the phosphorescent tones would function as a “warning light” for a westernization falsely savage). We note the detail of the twenty-four “cards”. So the “beautiful” glass window loses the concentration in a hall, and at most “makes smaller”, with the own screen, the facade on the road which has the neon signs, for the advertisement.